Stream strategies with Rational Team Concert 3.x

Note: This article was written with RTC 3.0 but the strategies and approaches to organizing projects and artifacts with Rational Team Concert are basic and are supported in every version of the tool. If you are unclear with some of the basic terminology that is presented here, you may want to start off by reading Getting Started with Rational Team Concert 3.x: A Deployment Guide.

Introduction

This guide provides examples of how to utilize and organize the stream capabilities of Rational Team Concert (RTC). It is designed to be a lightweight guide that will highlight some of the various different approaches that organizations use for managing code with RTC. Any one of the following approaches can be used by an organization, although you will find that your own implementation of a stream strategy is tailored to the needs and culture of your software development organization.

Single Stream Development

We sometimes refer to single stream development efforts as “straight line development”. This is the simplest form of software development, and it requires the least amount of administration and oversight. It is easy to set up, easy to understand, and works for well for small teams and organizations. We often see this style of stream strategy with IT shops, R&D efforts, and with teams that have an ongoing application maintenance effort.

In single stream development, all work is delivered to a single stream, which is associated with the project/team. Developers create one or more workspaces which deliver to this stream, as well as the sandboxes on their local machines which are related to these workspaces. Each developer/contributor works in their sandbox, and will check in their changes to their repository workspace. As change sets are created, they are associated with work items. When these work items are completed, their associated change sets are then delivered to the project/team stream, and a new baseline may be created.

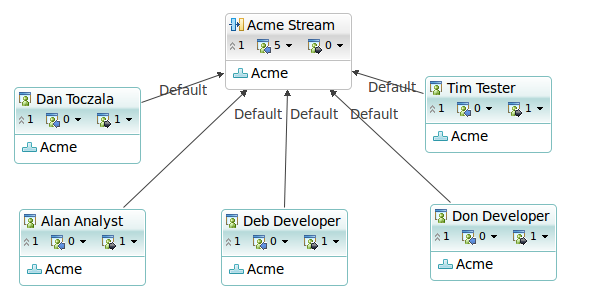

At this point these changes then become visible to the remainder of the team, who then will accept the incoming change sets. Figure 1 is a diagram of what a single stream strategy looks like when visualized in RTC. Note how each workspace is associated with an individual developer, tester, analyst or stakeholder, and all workspaces have the same project/team stream as their delivery target.

Figure 1 Single Stream Development

So each of the users (Alan, Deb, Dan, Don and Tim) has their own repository workspace. Any changes that they check in are only visible to them, and are stored in their repository workspace. Once those changes are ready to be shared with the rest of the team, they are delivered to the team stream (Acme Stream), and they will then appear as incoming changes for the remaining team members.

This is a very simple example, but it is easy to understand, easy to use, and still allows teams to manipulate change sets, track work items, automate builds, and do agile planning.

Naming Conventions

I need to take a slight detour here to address naming conventions. Naming conventions are critical to a successful deployment of Jazz. The tools don’t care what you name things, but since HUMANS need to interact with the tools, naming conventions become a critical piece of the solution. Good naming conventions will allow anyone interacting with the software development environment to easily navigate and find the files, information, and data that they are looking for. Table 1 shows a sample of some naming conventions that I have seen in use with organizations using RTC.

| RTC Element | Naming Convention | Explanation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Components | Xxx_comp Xxx_Xxx_comp | Components should be named in a way that developers will understand, and should follow what they currently call the software components. For example: My_Acme_comp | The “comp” suffix may be omitted. Names should begin with a capital letter, use underscores instead of spaces. |

| Streams | Xxx Xxx-Xxx | Streams should be named in a way that identifies the reason for the stream. For example: Acme-Integration, Acme-Release-3-0, Acme-Development. | Names should begin with a capital letter, use dashes instead of spaces. |

| Workspaces | proj_wkspc_userid_xx | Workspaces tend to have long names, with the project as the prefix, followed by “_wkspc_”, followed by the user ID, and then any other unique identifying information. For example: Acme_wkspc_dtoczala_dev, Acme_wkspc_dtoczala-maint, Acme_wkspc_integration_build | When workspaces are group owned, or used to perform CI builds, then substitute a meaningful description for the user ID. Workspaces should use underscores instead of spaces. |

| Plans | desc time Plan | Plans will have some descriptive piece telling what they are, the time period/iteration/release that they address, and then the word “Plan”. For example: Acme Sprint 1 Plan, Acme Release 2.0 Plan, Jade Team Sprint 7 Plan | Use spaces in plan names, avoid using underscores and dashes. |

The key to having useful and successful naming conventions is to have everyone using those naming conventions. They should be simple to remember, simple to use, and ease the understanding of the people using the tools. Complicated naming conventions get ignored. Don’t worry about handling every possible case with your naming conventions, that will make them too complex. There will always be exceptions to the naming conventions, just make sure the the goal of having naming conventions is met. The goal of this is to make things easier for the people using the software development environment.

Multiple Release Development

Some teams may be doing simple stream development, but they may need to support multiple releases of their software. We often refer to these types of efforts as Multiple Release Development, since the team is working on release X, but still needs to support and do maintenance for release x-1, x-2, and so on. This type of development effort is easy to set up within RTC. it requires some additional administration and oversight, as well as some increased discipline from the development team. We often see this style of stream strategy in organizations that produce software for sale (like RTC), or produce applications that have a non-server component. Embedded applications are a good example of this.

In multiple release development, developers may be expected to work on the new release, work on maintenance (bug fixes), or both. Developers will have to determine where most of their work is being done, so they can decide on how many Jazz workspaces to use, and where to base those workspaces. Teams need to have strong naming conventions for their streams and workspaces, in order to maintain a sense of order, and so everyone can easily find the things that they might be looking for. So once you have some good naming conventions in place, for the software components, the stream, and the workspaces, it is time to begin organizing those streams.

Everything begins with the streams. One approach is to have a dedicated development stream that is always working on the latest version. As releases are made, maintenance streams are formed and these begin with the released baselines and slowly change over time as maintenance activity continues.

Figure 2 Multiple Release Development Before

Just looking at what we see in Figure 2, we can immediately see how things are being done. I see the Acme development stream at the middle of this diagram, labeled as Acme-Development. I can see that Tim has a workspace that is based on the Acme development stream (called Acme_wkspc_tim_dev), and that his current and default targets for the delivery of any changes is the Acme development stream. Don and dtoczala have workspaces with similar relationships to the Acme development stream.

The interesting cases are those of Deb and Alan. Deb has a workspace (Acme_wkspc_deb_dev) that shows a dotted line relationship to the Acme development stream, but has a solid line and default relationship to the Release 1.0 stream, called Acme-release-1-0. The default tag indicates that this is her default delivery target, and the solid line indicates that this is also her current delivery target.

When we look at Alan’s workspace, we see that it is similar to the situation Deb is in, with Alan’s current delivery target being the Release 1.0 stream. What is different is that Alan’s default target for delivery is the Acme development stream (you can see the label on that arrow).

Note how the naming conventions we set up in Table 1 help make understanding these diagrams and change flows easier. This is a very simple example, imagine looking for specific information when there are hundreds of people involved in an effort. Naming conventions are critical in allowing us to maintain order and in keeping our development efforts organized.

Figure 3 Multiple Release Development After

Following the delivery, we have a new stream called Acme-release-1-1, which represents the code in the 1.1 release of our Acme component. Note that Deb now is doing maintenance work on Acme release 1.1, and Alan is doing maintenance work on Acme release 1.0. Both Dab and Alan have dotted lines coming from their workspaces, indicating that they also deliver change sets to alternative targets. The remainder of the team is still delivering their work to the Acme development stream.

One thing to note in Figure 3 is the direction of the flow of changes. In this scenario we show the changes flowing from the development stream to the two maintenance streams. The arrows could just as easily be pointing in the opposite direction, it just depends on where you initially make changes. In this scenario, we make our changes on the code currently being developed, and then flow those changes to the maintenance streams. In the case of Alan and Deb, they may deliver their changes to the maintenance stream first, and then deliver those same change sets to the current development stream. What is important here is that you show the relationships between the streams.

We typically recommend that changes flow from maintenance streams to the current development stream, since this is the way the work is typically done (I deliver my maintenance fix first, then I incorporate that fix into the current development stream). RTC will support flowing changes in either direction, so choose the one that best fits the way that you develop and maintain your software.

Another thing to note is the relationship between the streams. When you indicate a flow target for a stream, you must realize that this is just the identification of a relationship. There are no enforced semantics that are associated with this relationship. You cannot deliver changes from one stream to another, without first accepting these changes into a workspace.

Note: With release 3.0.1, the user now has the capability of adding a stream to be tracked in the Pending Changes view. From that view, you can deliver or accept changes between two streams, without first having to accept the change to a workspace. This only works when there are no conflicts, since resolution of a conflict requires a workspace.

The key here is the use of baselines (and snapshots) to identify key configurations. Each stream will have their own set of component baselines, which should represent the stable state of the stream at different points in time.

Multiple Application Development

When using Rational Team Concert with large scale development efforts, you may also be doing development of multiple software components or applications, which must then be integrated. In these situations, we use streams to segregate development efforts, and to control development environments.

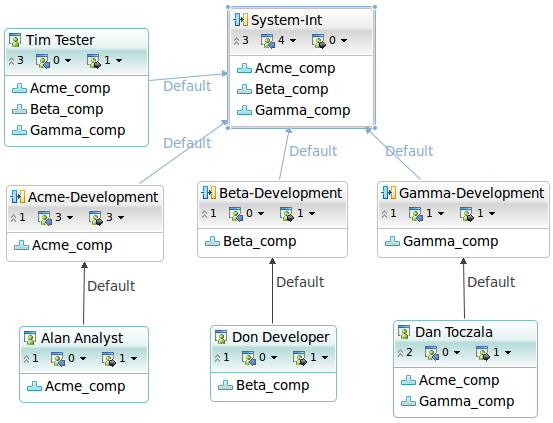

In Figure 4 we see a representation of our stream strategy. In this example I am showing the stream owners, and not the stream names. You can control this by checking and unchecking the “Show name instead of owner” checkbox in the Properties tab when you click on the workspace in the diagram.

Figure 4 Multiple Product Streams for System Integration

Sometimes these efforts on the individual components will require visibility to the other components available to the project. If you look at Dan’s workspace in the lower right of Figure 4, you will notice that Dan has both the Acme_comp and Gamma_comp in his workspace, but only the Gamma_comp component is available in the Gamma development stream. Dan will be able to build and test his work, but will be unable to deliver any changes to the Acme_comp component.

With this type of strategy, teams can work in isolation and integration activities can be coordinated without slowing development of the individual components or applications.

Using Side Streams

A “side steam” is something we do often in our own internal development efforts. We setup a side stream when we have a bigger feature that more than 1 person is working on which will span multiple milestones and has to be worked on in parallel with the larger release.In our example, suppose Alan & Tim are working on a new feature XYZ for Acme. They would setup a side stream called ACME – XYZ in progress stream that would collaborate with the main development stream. Alan & Tim can now be working on the parallel feature together, and share their changes between themselves in the ACME-XYZ side stream. Their work in progress is not visible to the rest of their team. They will periodically accept changes from the main stream and merge them in with their ongoing work. Once their feature is complete, they deliver the changes to the main development stream and delete the ACME – XYZ stream.

Using Streams to Represent Environments

In Figure 2 you can see an example of using streams to represent environments. The development stream reflects the state of the software in the development environment, while the release stream reflects the state of the software in the production environment. We something similar in Figure 4, when we see a variety of development streams which reflect the state of the software in the development environment, while we have a system integration stream which reflects the state of the systems integration environment.

Often you will see organizations use a mixture of approaches, as show in the examples in this article. Streams are a tool that is available to an organization to help you coordinate and organize work, and reflect the state of the various development and testing environments that an organization may have in use.

Conclusion

This article is meant to provide some basic strategies for managing software development efforts with Rational Team Concert. The strategies that your team uses will probably be a variant of one of these approaches. The key is to use the approach that best fits the needs of your organization. Remember that streams are a tool that you should use to make software development better organized, and to help make development activities as intuitive as possible.

Copyright © 2011, 2012 IBM Corporation

Discussion